Nara sake

Considered by many to be the birthplace of sake, Nara. It is around the end of the Muromachi period, in Nara, that techniques forming the basis for modern Japanese sake production became established.

Over the course of the Muromachi period, sake brewing techniques employed during the Heian period by brewers directly under the auspices of the Imperial Court, gradually came to be imparted to private breweries as well as temples in Nara, Kawachi and further afield. Temples built by the country during the Nara and Heian periods such as Kofukuji Temple, Todaiji Temple, and Shoryakuji Temple in Nara served as educational and political institutions during the Middle Ages.

During the Muromachi and Sengoku periods, after the Ōnin War, Sengoku daimyo (feudal rulers) suddenly rose to power in various locations, each establishing an independent state. Consequently, large temples could no longer rely on the imperial court or shogunate for financial resources. These temples then had to take measures to acquire funds, in a time which also saw a gradual transition to a money economy. One measure that was taken by such temples was the production of sake for sale.

The “Goshu no Nikki” (1489 or 1355), which is said to be Japan’s first technical book on sake brewing written by ordinary citizens, contains descriptions of not only how to make “goshu”, the name for the standard sake of the day, but also for making such sake types as “Amano Sake” and “Bodaisen”.

At the time, the sake made in temples was called “souboushu”. “Amano Sake” is a souboushu which was created at Amanosan Kongoji Temple, a temple of the Omuro School of the Shingon Sect, located in Amano-cho, Kawachinagano City, Osaka Prefecture. “Bodaisen” is a souboushu which was created at Bodaisan Shoryakuji Temple in Bodaisan-cho, a southeastern suburb of Nara City.

A description of the “Bodaisan tsubosen” is found in the “Kyougaku Shiyoshou” (1444) and it is understood that it was a major source of funding for the Daijoin cloister at Kofukuji Temple, at that time. In the middle of the 15th century, gifts were also bestowed upon the court nobility in the capital, and one sake that gained fame alongside Amano Sake was “Nara Sake”.

As sake was brewed at temples for the purposes of securing financial resources, they became places where knowledge concentrated, and with sufficient manpower, souboushu brewing methods evolved to eventually give rise to the “Morohaku” method.

In the process of establishing the “Morohaku” method, five elements that form the basis of modern brewing technology emerged, as detailed below.

-Use of White Rice-

First, is the use of white rice.

As a step in making sake, polishing the rice is something that is now taken for granted. This process is to remove proteins and oils from the outer layers of the rice to ensure that the fermentation process is easier to manage, and thereby produce a sake high in clarity.

By using white rice instead of brown rice, it became possible to brew sake that tasted much better. It is thought that during the Muromachi period rice was still being polished using foot-operated mortars. However, during the Edo period, the main production area for sake expanded to Nada in Hyogo where there was a shift from foot-operated mortars to polishing by waterwheel. As a result, not only could large quantities of rice be polished but high polishing rates could be achieved.

-Pressing-

The second element is the process of pressing.

The major factor that differentiates cloudy sake from clear sake (refined sake) is the process of pressing, known as “jousou”. Sake mash is put into cloth sacks which are then folded. Pressure is applied to the cloth sacks and the liquid that seeps through is “seishu” (refined sake). The solids that remain in the cloth sacks are the “sakekasu” (sake lees).

Through the process of pressing, the yeast, a fungi which ferment the rice solids and the sake, are left in the sakekasu. This puts the brakes on the fermentation process for the most part.

-Pasteurization-The third element is pasteurization.

After pressing, the clear sake is pasteurized. Through pasteurization, the activity of enzymes present in the liquid is stopped, enhancing product stability. These enzymes were made by the koji mould and are proteins that breakdown the rice into sugar. They remain in the sake until pasteurization continuing to change its taste profile. By stopping their activity through pasteurization, it is possible to preserve the desired taste.

After pasteurization, the sake was put in barrels, enabling distribution further afield. High-quality sake brewed at large temples could be supplied to distant places, enhancing its recognition.

-Yeast Starter-

The fourth element that became established is the concept of the yeast starter or “shubo”.

This is the process of cultivating the yeast required for making sake. The modern process of making shubo involves adding yeast to a small tank containing a mixture of steamed rice, koji rice and water with the objective of cultivating lots of healthy yeast.

Making a yeast starter would not have been essential before the usage of large wooden barrels (“ki-oke”) when sake was brewed in smaller vessels. However, as larger vessels came to be used in the brewing process, it is thought that shubo mashing came to be considered to be necessary to ensure the safe and stable production of sake. Sake would be made in small jars and pails and then used to start the fermentation process.

-Three-stage Mashing-

The fifth element is “three-stage mashing”.

Once the shubo is ready, more steamed rice, koji rice and water are added to it and mixed. The mixture is left until it shows healthy signs of activity, at which point steamed rice, koji rice and water are added again. On the following day, steamed rice, koji rice and water are added yet again for the last time.

In this way, these three ingredients are added to the mash in three stages called “hatsu-zoe”, “naka-zoe”, and “tome-zoe”. Each time the ingredients are added to the shubo, the condition of the mash is checked, and gradually the volume of the mash increases. This technique is also thought to have evolved as part of the Morohaku method. While vessels used in brewing remained small, all the ingredients could be mixed at once, but as large vessels came to be used, these ingredients had to be added in stages and in smaller quantities.

It is clear from the literature that, in this way, techniques that form the basis for modern refined sake production methods, emerged from Nara. While techniques were conveyed to other regions where they evolved further, it can be said with confidence that Nara is the birthplace of refined sake.

It is thought that the need to secure financial resources to fund the management of large temples drove the evolution of sake from its original “doburoku” (unpressed sake) form into its modern more stable and easily distributable refined form.

Today, we seek to build upon this foundation of techniques provided by our predecessors in Nara, making sake that can only be made in these times, and through this, we hope to pass down these techniques to coming generations.

Through our product “Takacho”, we hand down techniques and methods established at Bodaisan Shoryakuji Temple and other large temples in Nara, and we seek to pass down the traditions and formalities of Nara Sake to future generations.

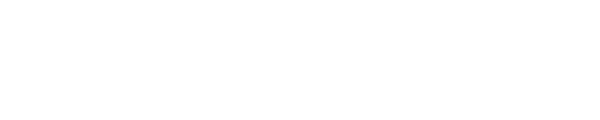

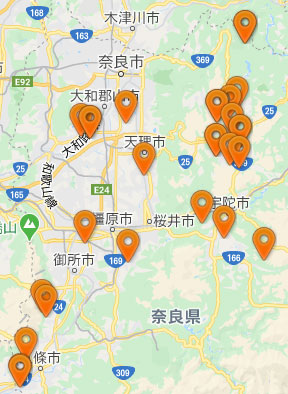

On the other hand, in producing “Kaze no Mori”, we continually embrace and incorporate the latest technology as well as rethink and renew traditional techniques. We endeavour to create new traditions and captivating new taste experiences.

We believe our calling to be the preservation of the traditional climate and culture of Nara, and that we can realize this through brewing sake in Nara and furthering its evolution across future generations.